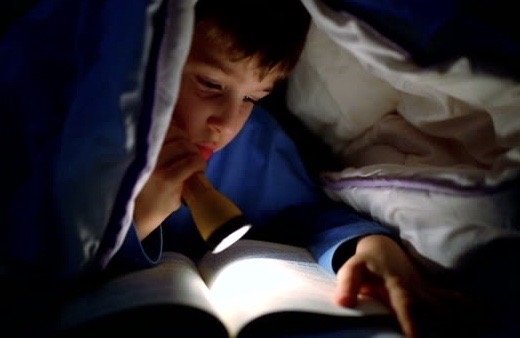

My parents instilled in me a deep affection for literature that commenced shortly after I had achieved the age of six, at which time I eagerly consumed “The Mayor of Casterbridge” by Mr. Thomas Hardy. Thoroughly enchanted by this captivating tale, I would remain awake throughout the night, a brazen violation of my parents’ bedtime decree (which they seldom enforced), my fingers flipping madly through the book’s magical pages, my head covered by a blanket emblazoned with images of barnyard animals, my sole source of illumination provided by a miniature flashlight.

Yes, this was the book that first awakened me to the wonders of fiction. I adored the sensuous feel of a book, the glorious musty smell of an old hardcover, the heft of a lengthy tome, the colorful symmetry of a regiment of volumes standing side by side on my bookshelves, the very act of turning pages. Thus I have always eschewed the use of flat, aesthetically barren electronic devices. From that point on, I devoured the works of Austen, Trollope, Dickens, Thackeray, and the Brontë sisters, eventually moving on to noted American scribes and those of other nationalities—Stendhal, Hugo, Dostoevsky, Mann, Marquez, Proust, Kafka, and all the rest. My gluttonous reading of the nineteenth-century British classics during my formative years resulted in my somewhat stilted and admittedly verbose manner of speaking which, in my youth, was nearly incomprehensible to most of my young classmates and often considered snobbish, although that was never my intention. Simply put, I have always harbored a distaste for the vernacular as well as all manner of slang, both of which I find somewhat pedestrian.

Yes, I was a precocious lad, beloved by my grade school teachers for my superior intellect, flawless grooming (I customarily sported a starched white shirt and bow tie to class), and admirable behavior (I was a quiet, brooding sort of young man who caused no disruption in class). Yet to my dismay, my mostly gushing report cards (written in a loopy cursive mode of handwriting and frequently containing a few minor but egregious misspellings or questionable grammar), there was always a sentence or two regarding my profound lack of social skills—“Ishmael would benefit from more interaction with his schoolmates. He seems to be quite shy.”

Having consumed many of the classics, I found it somewhat absurd that in grade school I was expected to read and discuss a thirty-page, poorly illustrated, ineptly plotted book involving the insipid escapades of various dimwitted characters and their equally insufferable pets. Simply put, I was entirely devoid of friends, as my schoolmates and their activities held no interest for me. The only connection I had to those in my age group consisted of a passion for such delicacies as Snickers chocolate bars, Black Vines Licorice Twists, Twinkies, Cheese Puffs and other items one might describe as unhealthy victuals, but that was the full extent of my shared interest. As this was insufficient to inspire a true connection with my colleagues, I remained virtually friendless during those early days of my education.

And so I invariably ate alone in the school cafeteria, my briefcase by my side, consuming the repast (which usually consisted of a ham and cheese sandwich) that my mother had hurriedly prepared for me the night before, and filling the remaining time with the perusal of a book. Although I later made several acquaintances during my teenage years in high school—most participated, simply to eliminate that last annoying sentence from my report cards, a failure that so displeased Mother and Father.

Besides, croquet seemed like a simple, civilized pastime, one that would require an economy of movement and an inconsequential risk of injury, not that I would have excelled at it. It was an abysmal waste of time of course, but perhaps a strategy with which to improve my woefully inadequate social skills.

“I hate to tell you this, Ishmael, but I’m afraid croquet will not become part of the school’s athletic curriculum,” Mr. Ramsey, the school’s gym teacher, said one afternoon as I sat quite alone in the school cafeteria. I had by that time submitted a formally written request that a croquet team be organized. In spite of my aversion to sports I had a fondness for Mr. Ramsey, who took a great liking to me and thus violated school regulations by allowing me to abstain from gym class activities, mostly because I was so pathetically inept at them. He, too, was an avid reader but I had no idea what sort of literature lined his bookshelves, not that it mattered, mattered, for Mr. Ramsey was my sole friend.

“I am not surprised to hear that, Mr. Ramsey,” I said. “Truth be told, I held out little hope for the acceptance of my application, but I am most thankful that you were kind enough to propose it for me.”

“Well, I’m sorry,” he said, with sympathy in his tone. “Principal Thorndyke didn’t think standing around hitting wooden balls through hoops was good exercise.”

Although this was the precise reason I had suggested that the school adopt the sport, I did not address his citation of Principal Thorndyke’s reasoning. “C’est la vie,” I said. “But I fear my parents will be quite displeased by this news.”

“Why is that?”

“Because, alas, it appears that I have no friends,” I said.

“Well, you’re not the only one.”

“Oh?” Mr. Ramsey glanced around the room and I followed his gaze until it fell upon a young bespectacled fellow who sat at a nearby table. I observed that he was quite alone as he consumed his lunch with great concentration, his eyes squarely fixed upon a yellow cupcake as if it were an ancient relic from an archaeological exploration. It appeared that he was myopic as he held said cupcake two inches away from his visage.

“That’s Jerome Duckworth,” Mr. Ramsey told me. “He’s a loner too. Maybe you two could eat at the same table. He doesn’t talk much.”

“Hmm,” I said. “Perhaps this suggestion is worthy of consideration.” I placed a bookmark in the novel I had been perusing. Mr. Ramsey peered over my shoulder.

“What are you reading today, Ishmael?”

“Dead Souls by the Russian author Mr. Nikolai Gogol.”

He nodded. “Sounds like a hoot.” I chuckled at his witticism. Just then the first warning bell rang signaling the end of the lunch hour, so I folded up the remains of my lunch in the tin foil my mother had wrapped it in and placed the novel in my briefcase.

“You sure do a lot of reading, Ishmael,” Mr. Ramsey said. “Every time I see you, you’ve got your nose in a book.””

““Reading is my primary form of gratification, ” I said. “Yet I also do it for inspiration.” I glanced around at my schoolmates as they sucked noisily through the straws in their miniature milk cartons and then proceeded to unload their trays into the trash receptacles.

“Inspiration for what, Ishmael?”

“For my work.”

“You mean your homework?” I hesitated. Should I tell him? Would he laugh or make a condescending remark? After all, I was only eight.

“No,” I said. “A slightly more formidable project.”

“And what would that be, if you don’t mind me asking?”

“Do not inform a soul, but I have recently commenced writing the Great American Novel!”

He raised an eyebrow. “Is that so? I must say, I like your ambition, Ishmael. It’s very admirable for a young fellow like you to think big. I look forward to reading it.”

“Thank you,” I said. I had yet to inform my parents of my lofty goal for fear that they would find it a trifle too ambitious and therefore discourage me from undertaking it at such an early age. Mr. Ramsey’s encouragement was most welcome.

“What’s it about?” he asked.

I looked at Mr. Ramsey. In some ways he reminded me of Charles Bingley, Miss Jane Austen’s delightful fictional character, in that he was a cheerful fellow, although the whistle that resided around Mr. Ramsey’s thick neck was not a fashion accessory Mr. Bingley would have sported. “I am not entirely certain of that yet, Mr. Ramsey,” I said. “Perhaps a memoir disguised as fiction. Something along those lines.””

““A memoir, huh?” he said. “But you’re kinda young, Ishmael. Have you had a lot of memorable adventures?”

I gave this some thought and said, “Well, I once purloined a package of Hostess Ding Dongs from a convenience store.”

He appeared to be stifling a chuckle. “Why?”

“I had just completed reading ‘Oliver Twist’ by Mr. Charles Dickens and I wished to experience the art of theft, although I did not possess the derring-do to attempt the picking of pockets. Please do not tell anyone as I do not wish to be taken into custody by the local constabulary.”

“I won’t,” he said. His expression told me that he was being truthful. “So how far have you gotten in this book you’re writing?”

I removed my spectacles and wiped them with a napkin. “Alas, at the moment I have written only two words.”

“And what might those be?”

“The word ‘Chapter’ and the word ‘’One.’ I have not yet decided whether or not to pen the words ‘Part’ and ‘One,’ but I may do so, thus doubling my word count.””

“Well, you’re off to a good start,” he said with a smile. As the second warning bell sounded, he put an arm around my shoulders and together we ambled out of the cafeteria and into the commotion of the hallway.